Deprenyl – an antiaging, life-extending aphrodisiac (update)

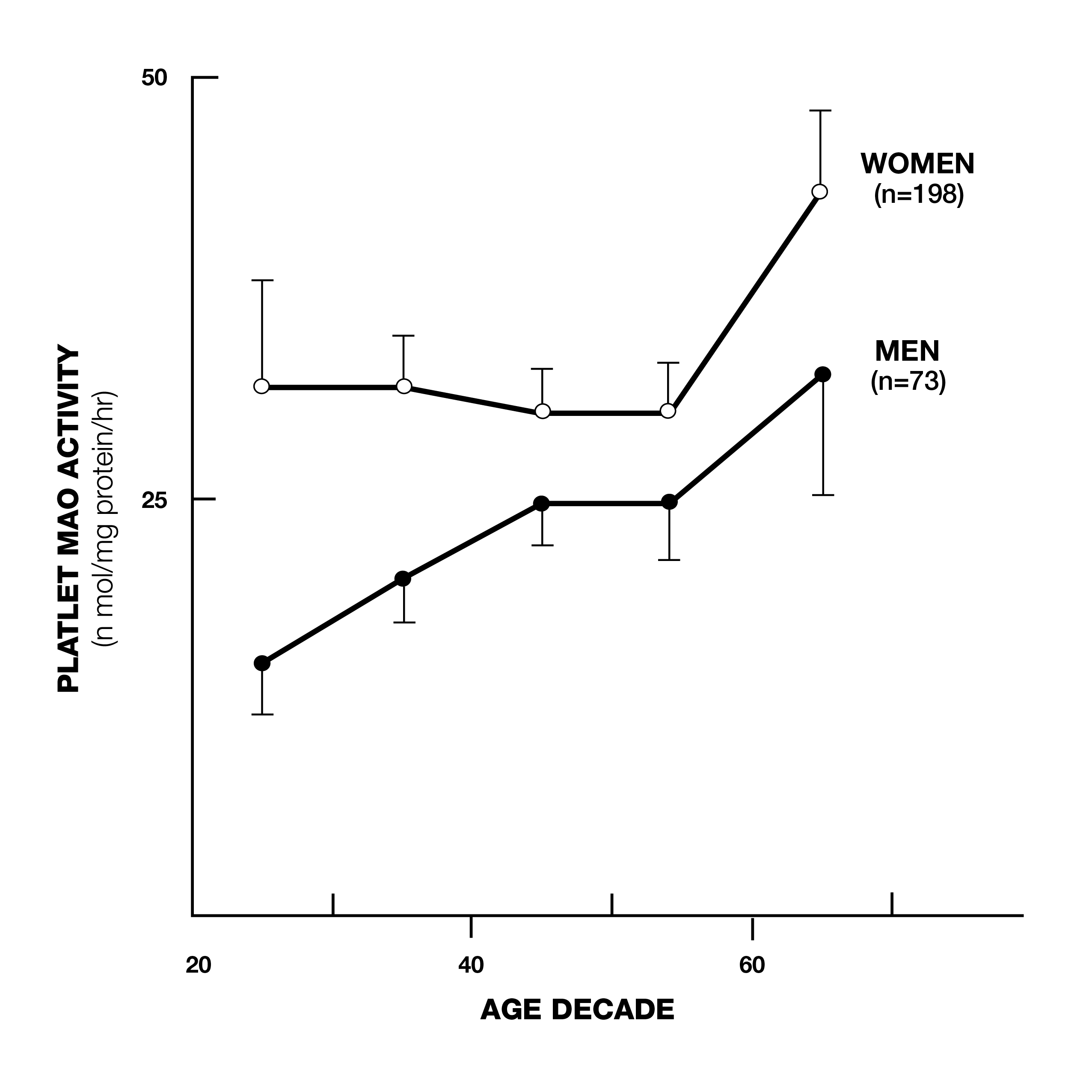

Deprenyl (later known as selegiline) was developed by Professor Josef Knoll of Semmelweis University in Hungary in the 1950s. It was first used as an anti-depressant and was later used for the prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s and (especially) Parkinson’s Disease. Deprenyl’s value initially was based on the belief only that it was a monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibitor. MAO-B is an enzyme that degrades the neurotransmitters dopamine, epinephrine, nor-epinephrine and serotonin in the brain. MAO-B levels rise with age (Fig. 1)1 and it was believed that this caused a decrease in these neuro-transmitters, which resulted in depression, Parkinsonism, and other neurodegenerative diseases. By selectively inhibiting MAO-B, deprenyl was theorized to maintain these neuro-transmitters at more youthful levels.

Life-extending effects

In 1983, Dr. Walter Birkmayer in Germany reported that Deprenyl, combined with L-dopa, not only improved the on-off phases and rigidity of Parkinson’s disease and reduced adverse reactions to L-dopa, but also prolonged the life expectancy of Parkinson’s patients!2 Birkmayer’s preliminary report was confirmed by ten-year long studies in nearly 1,000 Parkinson’s patients- who added deprenyl to their regimens after L-dopa had lost its efficacy.3-6 The L-dopa-plus-deprenyl-regimen significantly delayed the progression of Parkinson’s symptoms, and increased life expectancy compared to those on L-dopa alone.

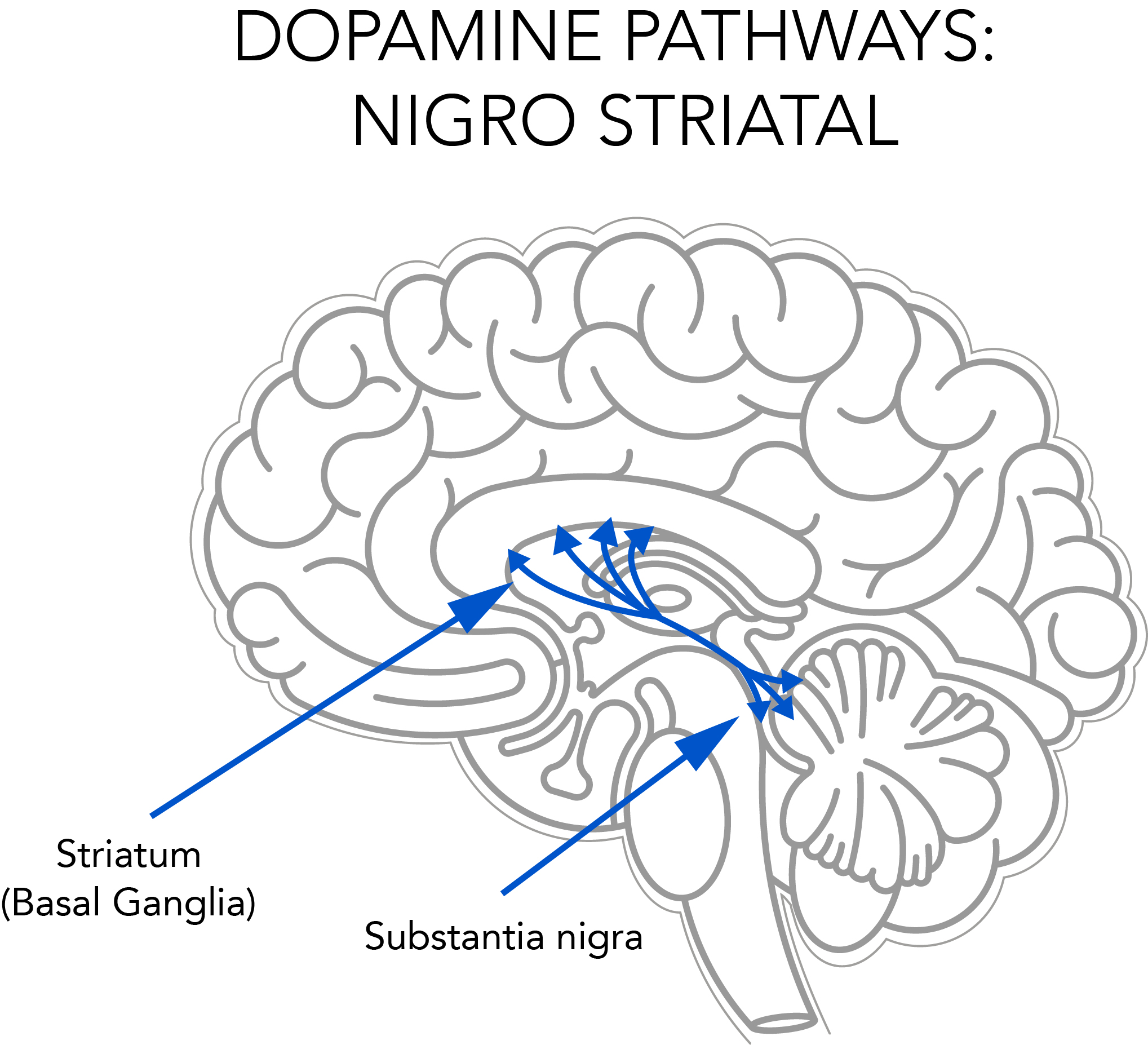

Autopsies showed that deprenyl prevented or retarded the degeneration of striatal dopaminergic neurons in the brain (see Fig. 2). Scientists in the U.S.7 and Finland8 recommended that Deprenyl treatment be started as soon as the Parkinson’s diagnosis was made.

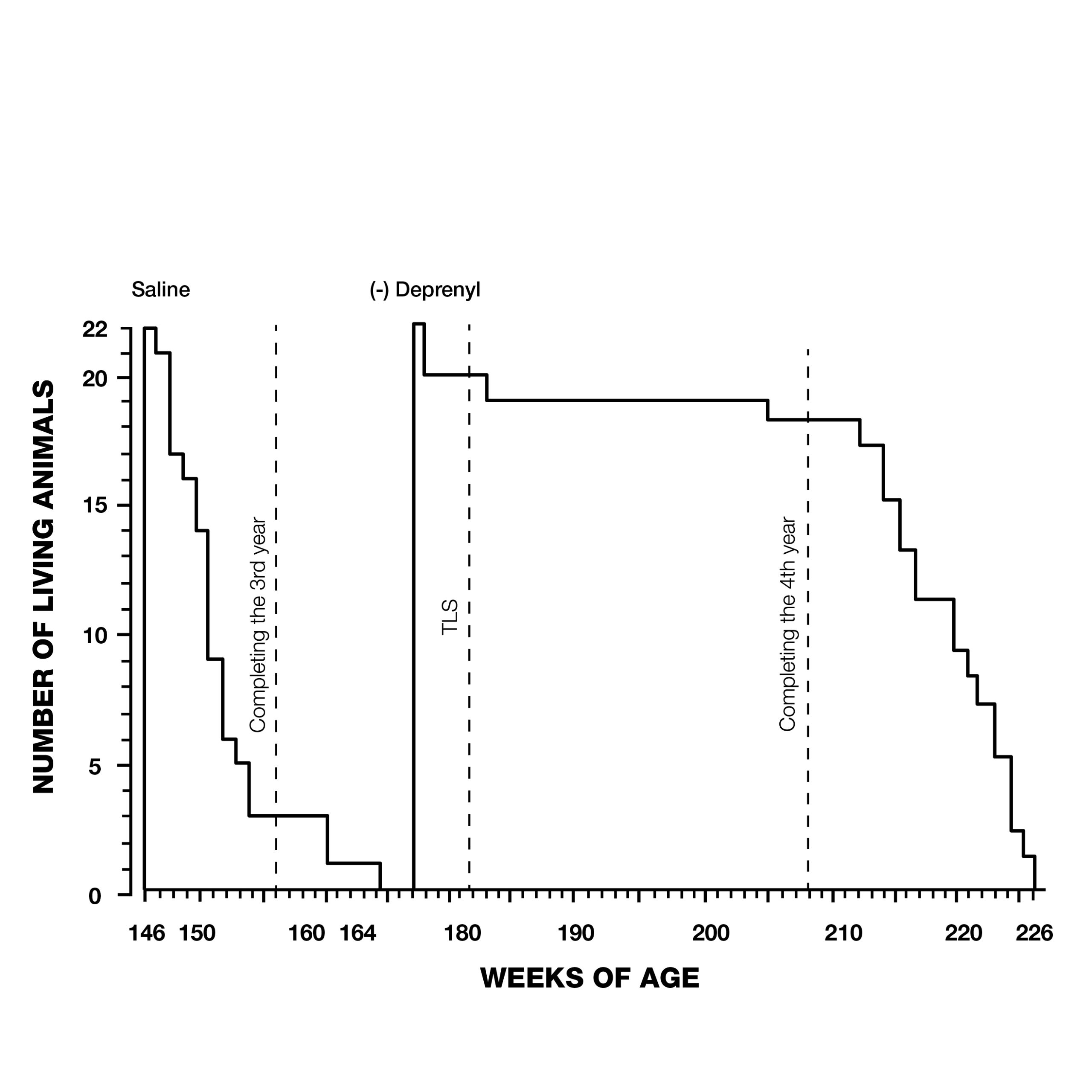

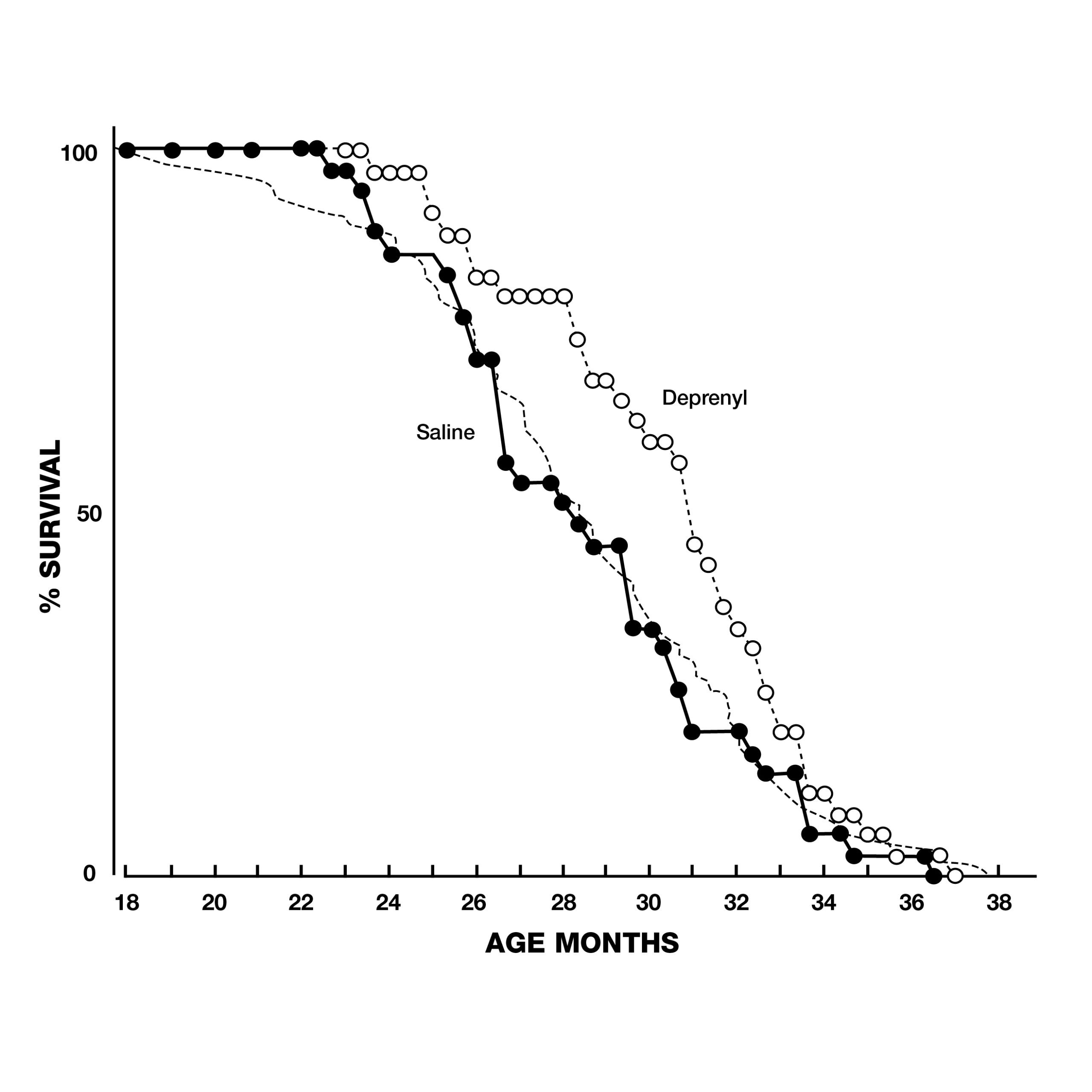

But it wasn’t just Parkinson’s patients that were living longer with deprenyl. In 1988, Knoll rocked the gerontological community with a study that showed a dramatic extension of maximum lifespan of rats treated with deprenyl (Fig. 3).9

Knoll and his colleagues treated 132 24-month-old male rats, (equivalent to 60-year-old humans) with injections of saline or deprenyl three times/week. The average lifespan of the saline-treated group was 147 weeks. The oldest rat in the saline group was 166 weeks old when it died. In contrast, the first rat to die in the deprenyl group lived 171 weeks, (five weeks after the last control rat died), and the longest-living deprenyl-treated rat died in its 226th week! The average lifespan of the deprenyl-treated group was 198 weeks–i.e., higher than the previously-estimated maximum lifespan of the rat (182 weeks). Knoll claimed that this was the first time that administration of a drug or nutrient resulted in extension of a species’ known maximum lifespan.10

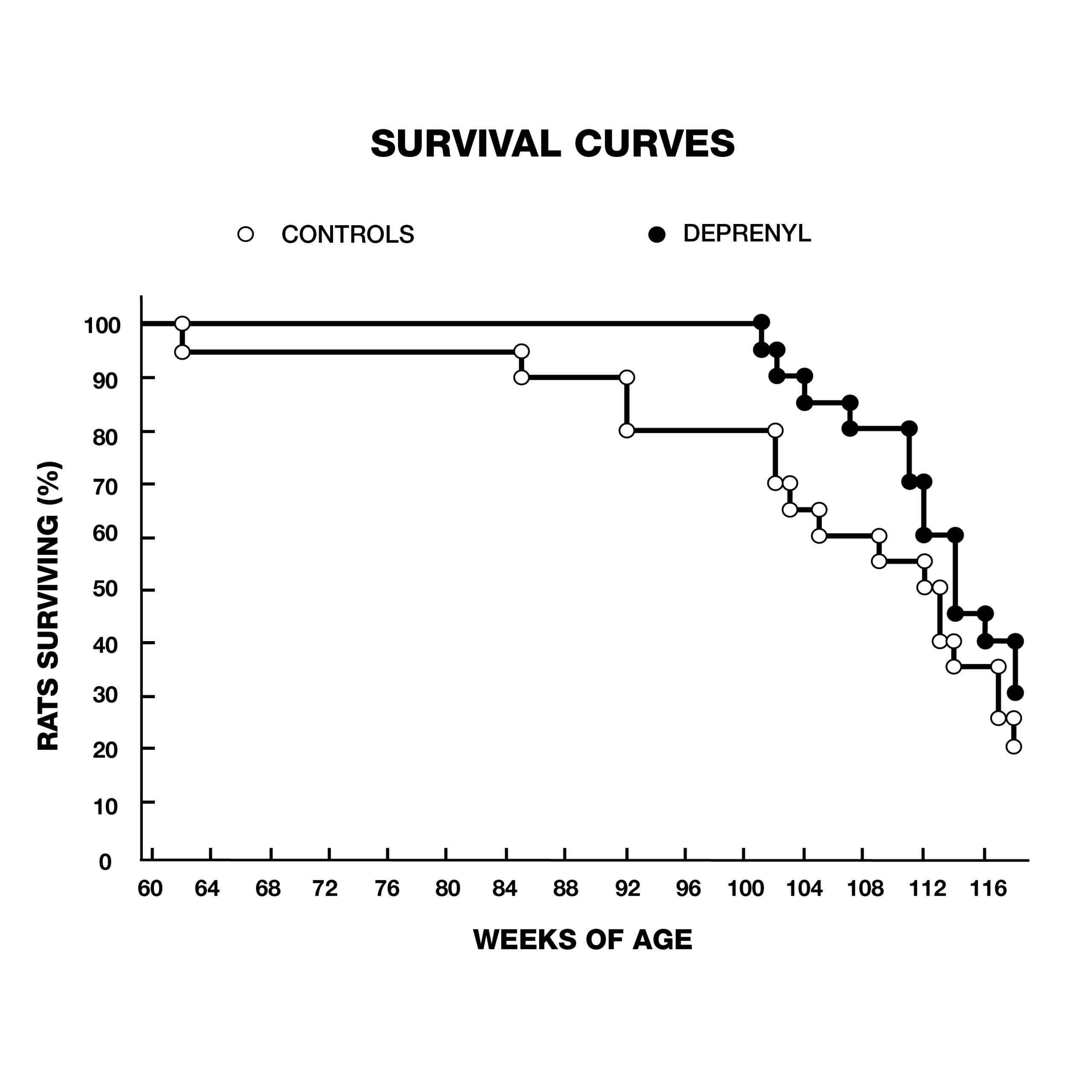

In addition to these dramatic findings, the scientists evaluated sexual functioning in the rats, as a measure of their brain striatal function. Because of the normal age-related decay of sexual function, none of the 2-year-old animals displayed full-scale sexual activity. In the saline group, the last signs of sexual activity had completely vanished by the 33rd week of treatment. In contrast, deprenyl treatment restored full-scale sexual activity in 64 out of 66 rats!11 Inspired by Knoll’s groundbreaking lifespan studies with deprenyl, researchers around the world began trying to duplicate his results in a variety of species. Researchers at the University of Toronto in Canada gave injections of deprenyl (0.25 mg/kg) or saline every other day to male Fischer rats starting at 23 to 25 months of age. The deprenyl-treated animals showed a significant increase in both mean and maximum survival.12 Scientists from the Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontology reported their results with 70 male Fischer 344, (F-344) rats treated with injections of deprenyl or saline 3 times a week from the age of 18 months until they died. Although their results were not as dramatic as Knoll’s, the average lifespan of deprenyl-treated rats after 24 months was 34% greater than saline-treated controls, lending support to the growing awareness of deprenyl’s life-extending properties (Fig. 4).13, 14

In Germany, scientists treated 14 immunosuppressed mice- beginning at 2 ½ months of age, with half the group receiving deprenyl-laced food. The last mouse in the control group died at the age of 5 months (2.5 months after the study began). In contrast, the last mouse in the deprenyl group died at the age of 14.5 months–1 year after the beginning of the study, having lived nearly three times as long as the longest-living control mouse!15

Scientists at the Jackson Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, conducted studies on 2 strains of mice, starting at mean ages of 26 and 18.5 weeks. In the study that began at 26 weeks, there was a 77-day increase in mean female lifespan, and an 84-day increase in mean male lifespan. For the mice that began treatment at 18.5 weeks of age, the mean longevities were increased only 59 days in females, and 56 days in males. Despite the inconsistencies, the authors concluded that since all studies found increased lifespans in deprenyl-treated mice, further research with deprenyl as a life-extending substance was justified.16

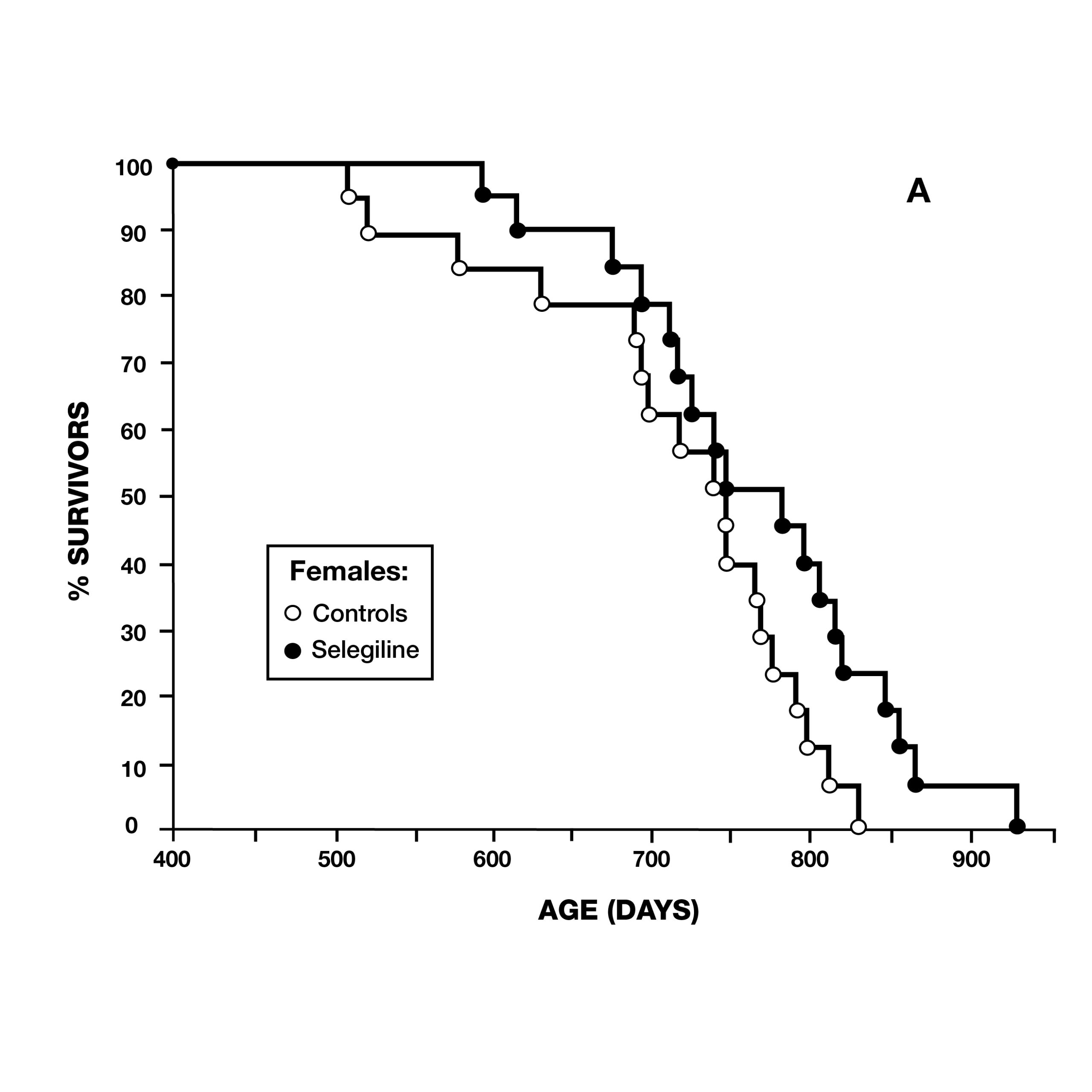

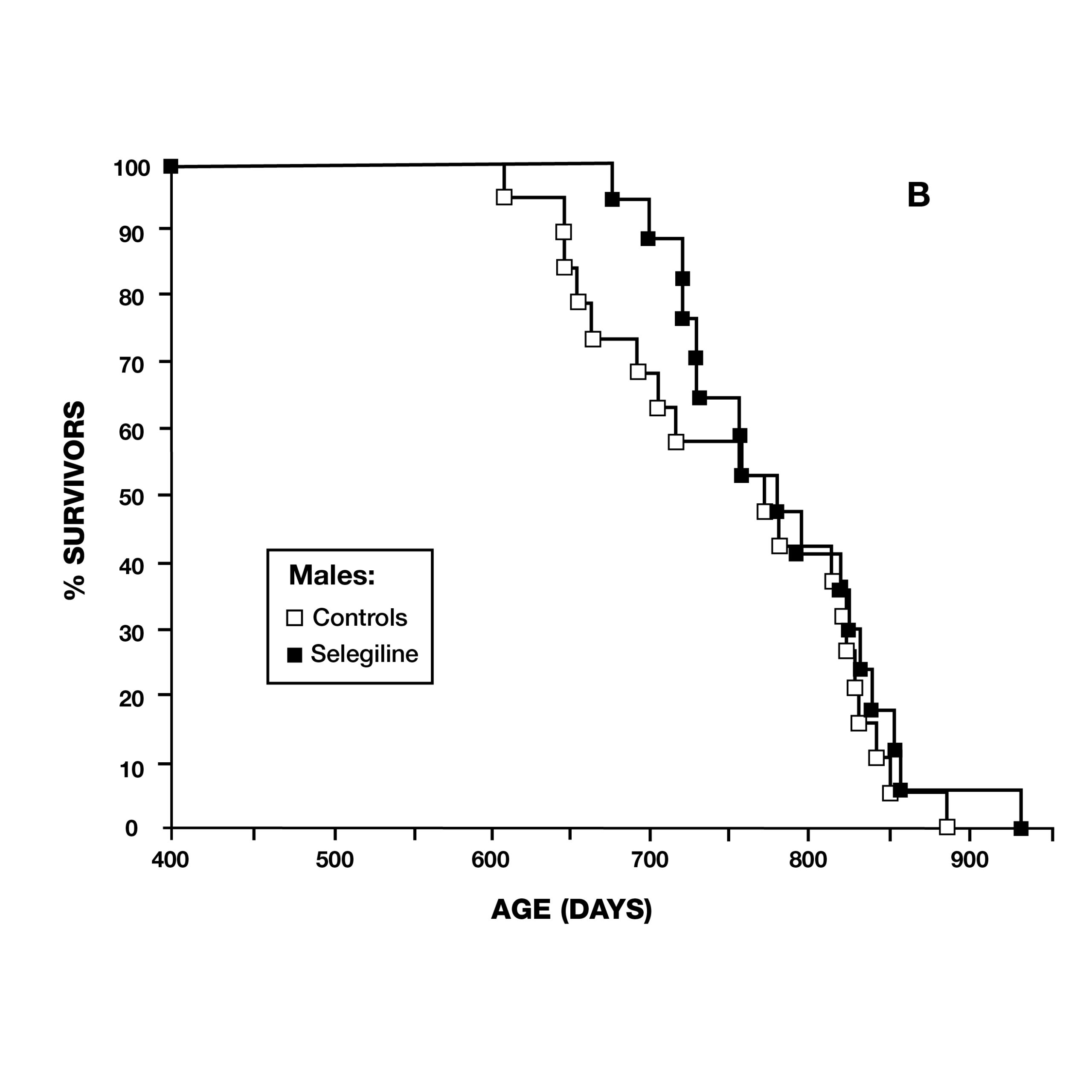

In 1997, a team from Mannheim, Germany, reported on deprenyl’s effect on the lifespan of Syrian Hamsters. At the age of 13 months, 36 pairs of hamsters were treated–half of which received 0.05 mg/kg deprenyl in their food. The scientists surprisingly found that deprenyl significantly increased life span in the females, but not in males (Fig. 5).17 This was especially significant as females of this species normally had a shorter lifespan than males.

Two months later, the same journal published a study by scientists at the VA Medical Center in Denver, CO, using male Fischer 344 rats. They administered deprenyl in drinking water to 14 rats, beginning at 54 weeks of age (16 rats served as controls) (Fig. 6). Although there was no difference in the maximum lifespan due to deprenyl, the mean lifespan was significantly longer for the deprenyl-treated rats (110 vs. 103.5 weeks).18

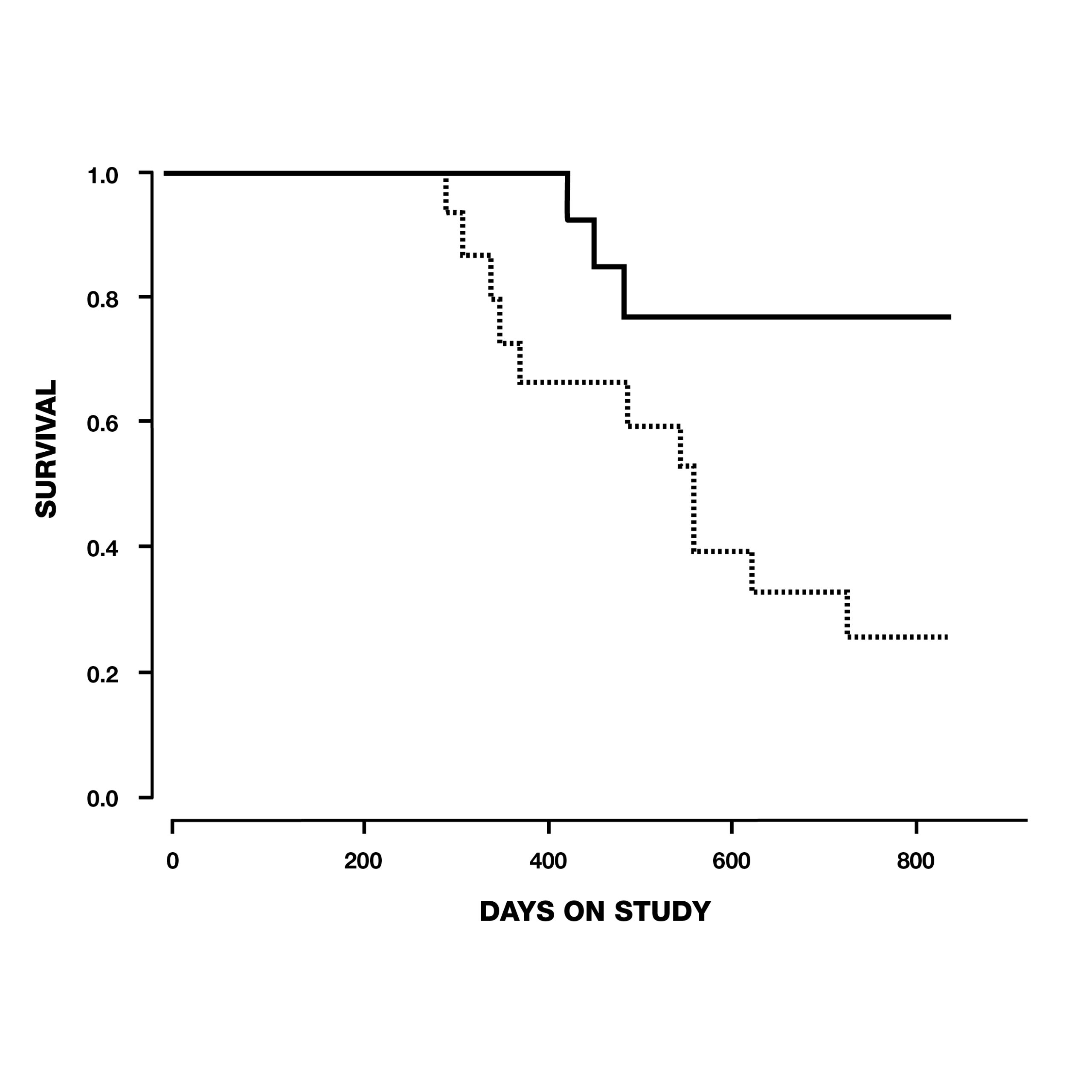

In the same year, thirty-three elderly beagle dogs between the ages of 10-15 years old were given 1 mg/kg of deprenyl or a placebo each day for 104 weeks by researchers in Overland Park, Kansas. Twelve of 15 (80%) dogs in the deprenyl group survived to the conclusion of the study, in contrast to only 7 of 18 (39%) of the dogs who received placebo. By the time the first deprenyl-treated dog died on day 427, five placebo-treated dogs had already succumbed–the first on day 295 (see Fig. 7). The authors concluded that daily administration of 1 mg/kg deprenyl could prolong the life of relatively healthy 10-15-year-old dogs.19

The German team that three years previously had tested deprenyl on immunosuppressed NMRI mice (cited above) did another series of experiments using various combinations of deprenyl and lipoic acid in ten groups of 14 mice. They obtained the best results with doses of 75 mcg/kg deprenyl plus 9 mg/kg of R-lipoic acid. This combination resulted in nearly 200% increased maximum lifespan!20

Multiple mechanisms for Deprenyl’s benefits

Besides its known MAO-B inhibiting properties, scientists in the UK reported that deprenyl also induced increased levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and suggested this as the basis of deprenyl’s neuroprotective and life-extending effects.21

The Japanese team led by Kitani has probably done more ongoing research with deprenyl’s effect on lifespan than any other group. Kitani speculated that the life-extending effects of deprenyl were not due solely to its MAO-B inhibiting effects, but to a multiplicity of mechanisms. These included elevations of catalase as well as SOD (as found by the British team mentioned above). Other benefits attributed to deprenyl included immune system enhancement characterized by increased concentrations of cytokines such as interleukin-1beta (IL-1beta), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), interferon-gamma, and natural killer (NK) cell functions. Kitani speculated that these humoral factors were responsible for deprenyl’s ability to prevent malignant tumors in rodents and dogs, and for its diverse antiaging and life-prolonging effects by enhancing homeostatic regulation of the neuro-immuno-endocrine axis.22-26

Researchers from the Department of Pharmacology, University of North Dakota School of Medicine and Health Sciences expanded upon deprenyl’s potential life-extending mechanisms by noting that deprenyl also enhances cyclic AMP; restores insulin-like growth factor I (IgF1); possesses neurotrophic-like actions and enhances the synthesis of nerve growth factor; and protects against peroxynitrite- and nitric oxide-induced apoptosis.27

Less may be more

When deprenyl was first clinically used, the recommended dose for Parkinson’s disease was 5 mg in the morning, followed by a second dose at noon. Prof. Knoll early-on recommended that those at risk of (or diagnosed with) Alzheimer’s disease “should take 10 mg daily for the rest of their lives.”28 This is probably still good advice for those suffering from these dementing illnesses.

However, Kitani and his associates found that with continued use, lower doses of deprenyl provided better effects with regard to optimizing antioxidant enzyme levels in the brain and maximizing the life expectancy and lifespan of experimental animals. They determined that the dosage used for any life span study was a critical factor, with the dosage differing widely depending on sex, age of the animal, and duration of therapy. In fact, Kitani’s team proposed that long-term treatment with deprenyl decreased the optimal dose by a factor of at least 5 in terms of upregulation of antioxidant enzymes.29, 30 Although Dr. Kitani had conducted more studies with deprenyl than any other scientist except Prof Knoll, there is no indication that he used deprenyl himself. He passed away unexpectedly on October 15th, 2008 at the age of 73 from colon cancer.31

Kitani’s conclusions agree with Knoll’s later recommendations. Whereas Knoll initially recommended dosages of up to 10 mg per day for those with Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases, he explained in his later work that deprenyl has enhancing qualities in “femto-picomolar concentrations,” which leave MAO-B activity unchanged. He believed that the activity of the catecholaminergic neurons in the brain stem and this previously unrecognized ‘enhancer effect’ is responsible for the unique therapeutic benefits of deprenyl. Consequently, Knoll suggested doses of as little as 1 mg/day as optimal for disease-prevention and life-extending purposes.32, 33

Prof. Knoll ‘practiced what he preached.’ Since January 1989, at the age of 64, he took 1 mg Deprenyl every day. At the age of 92, he continued his daily consumption of what he referred to as a catecholaminergic activity enhancer (CAE) substance. I first discussed this with him at the IAS-sponsored Monaco Anti-Aging Conference in 2002. He revealed that although deprenyl’s activity as a MAO-B inhibitor was its first-discovered and most highly-promoted mechanism, he described its most important mechanism as a “catecholaminergic receptor sensitizer”– sort of like a; “metformin for the brain” (he winked at me as he said that, as I had just given a talk on the multi-hormone receptor-sensitizing effects of metformin).

Until his death on April 17th, 2018 at age 94, Prof. Knoll continued to maintain his emeritus position as a Professor at Semmelweis University, conducted ongoing research and wrote books and articles. His only limitation was that he traveled less internationally than he had formerly done. He commented slyly in his book that his ongoing “self-experiment (1 mg of Deprenyl daily) augers very well.”33

References:

- Robinson DS, Nies A. Demographic, biologic, and other variables affecting monoamine oxidase activity. Schizophr Bull. 1980;6(2):298-307.

- Birkmayer W. Deprenyl (selegiline) in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1983;95:103-5.

- Birkmayer W, Knoll J, Riederer P, Youdim MB, Hars V, Marton J. Increased life expectancy resulting from addition of L-deprenyl to Madopar treatment in Parkinson’s disease: a long-term study. J Neural Transm. 1985;64(2):113-27.

- Youdim MB. Pharmacology of MAO B inhibitors: mode of action of deprenyl in Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1986;22:91-105.

- Sandler M. Deprenyl in perspective: prophylaxis for Parkinson’s disease? J Neural Transm Suppl. 1986;22:107-15.

- Birkmayer W, Birkmayer GD. Effect of deprenyl in long-term treatment of Parkinson’s disease. A 10-years’ experience. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1986;22:219-25.

- Yahr MD. Deprenyl and parkinsonism. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1987;25:5-12.

- Rinne UK. Deprenyl as an adjuvant to levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1987;25:149-55.

- Knoll J. Extension of life span of rats by long-term deprenyl treatment. Mt Sinai J Med. 1988 Jan;55(1):67-74.

- Knoll J. The striatal dopamine dependency of life span in male rats. Longevity study with deprenyl. Mech Ageing Dev. 1988 Dec;46(1-3):237-62.

- Knoll J, Dallo J, Yen TT. Striatal dopamine, sexual activity and lifespan. Longevity of rats treated with deprenyl. Life Sci. 1989;45(6):525-31.

- Milgram NW, Racine RJ, Nellis P, Mendonca A, Ivy GO. Maintenance on Deprenyl prolongs life in aged male rats. Life Sci. 1990;47(5):415-20.

- Kitani K, Kanai S, Sato Y, Ohta M, Ivy GO, Carrillo MC. Chronic treatment of deprenyl prolongs the life span of male Fischer 344 rats. Further evidence. Life Sci. 1993;52(3):281-8.

- Kitani K, Kanai S, Carrillo MC, Ivy GO. Deprenyl increases the life span as well as activities of superoxide dismutase and catalase but not of glutathione peroxidase in selective brain regions in Fischer rats. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994 Jun 30;717:60-71.

- Freisleben HJ, Lehr F, Fuchs J. Lifespan of immunosuppressed NMRI-mice is increased by deprenyl. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1994;41:231-6.

- Archer JR, Harrison DE. L-deprenyl treatment in aged mice slightly increases life spans, and greatly reduces fecundity by aged males. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996 Nov;51(6):B448-53.

- Stoll S, Hafner U, Kränzlin B, Müller WE. Chronic treatment of Syrian hamsters with low-dose selegiline increases life span in females but not males. Neurobiol Aging. 1997 Mar-Apr;18(2):205-11.

- Bickford PC, Adams CE, Boyson SJ, Curella P, Gerhardt GA, Heron C, Ivy GO, Lin AM, Murphy MP, Poth K, Wallace DR, Young DA, Zahniser NR, Rose GM. Long-term treatment of male F344 rats with deprenyl: assessment of effects on longevity, behavior, and brain function. Neurobiol Aging. 1997 May-Jun;18(3):309-18.

- Ruehl WW, Entriken TL, Muggenburg BA, Bruyette DS, Griffith WC, Hahn FF. Treatment with L-deprenyl prolongs life in elderly dogs. Life Sci. 1997;61(11):1037-44.

- Freisleben HJ, Neeb A, Lehr F, Ackermann H. Influence of selegiline and lipoic acid on the life expectancy of immunosuppressed mice. Arzneimittelforschung. 1997 Jun;47(6):776-80.

- Glover V, Clow A, Sandler M. Effects of dopaminergic drugs on superoxide dismutase: implications for senescence. J Neural Transm Suppl. 1993;40:37-45.

- Carrillo MC, Kitani K, Kanai S, Sato Y, Miyasaka K, Ivy GO. The effect of a long term (6 months) treatment with deprenyl on antioxidant enzyme activities in selective brain regions in old female Fischer 344 rats. Biochem Pharmacol. 1994 Apr 20;47(8):1333-8.

- Kitani K, Miyasaka K, Kanai S, Carrillo MC, Ivy GO. Upregulation of antioxidant enzyme activities by deprenyl. Implications for life span extension. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996 Jun 15;786:391-409.

- Kitani K, Kanai S, Ivy GO, Carrillo MC. Assessing the effects of deprenyl on longevity and antioxidant defenses in different animal models. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998 Nov 20;854:291-306.

- Kitani K, Minami C, Yamamoto T, Kanai S, Ivy GO, Carrillo MC. Pharmacological interventions in aging and age-associated disorders: potentials of propargylamines for human use. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002 Apr;959:295-307.

- Kitani K, Minami C, Isobe K, Maehara K, Kanai S, Ivy GO, Carrillo MC. Why deprenyl prolongs survivals of experimental animals: increase of anti-oxidant enzymes in brain and other body tissues as well as mobilization of various humoral factors may lead to systemic anti-aging effects. Mech Ageing Dev. 2002 Apr 30;123(8):1087-100.

- Ebadi M, Brown-Borg H, Ren J, Sharma S, Shavali S, El ReFaey H, Carlson EC. Therapeutic efficacy of selegiline in neurodegenerative disorders and neurological diseases. Curr Drug Targets. 2006 Nov;7(11):1513-29.

- Knoll, J. Selegiline medication: A stratey to modulate the age-related decline of the striatal-dopaminergic system. J Am Geriatr Soc. 40(8):839-47, August 1992.

- Kitani K, Kanai S, Miyasaka K, Carrillo MC, Ivy GO. Dose-dependency of life span prolongation of F344/DuCrj rats injected with deprenyl. Biogerontology. 2005;6(5):297-302.

- Kitani K, Kanai S, Miyasaka K, Carrillo MC, Ivy GO. The necessity of having a proper dose of deprenyl (D) to prolong the life spans of rats explains discrepancies among different studies in the past. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006 May;1067:375-82.

- Nagy I-Z, Goto S. In Memorium, Kenichi Kitani (1938-2008). Arch Ger and Ger 48(2009)269-270.

- Miklya I. [Slowing the age-induced decline of brain function with prophylactic use of deprenyl (Selegiline, Jumex). Current international view and conclusions 25 years after Knoll’s proposal]. Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 2009 Dec;11(4):217-25.

- Knoll, J. How selegiline (deprenyl) Slows Brain Aging (English Edition), 2012. Bentham Science Publishers, Oak Park, IL.

Captions for Figures:

Fig. 1. Platelet MAO-B increases with age.1

Fig. 7. Survival of dogs between 10 and 15 years old at the start of the study, treated with deprenyl for at least six months. Note that by the time the first deprenyl-treated dog died on day 427, five of the placebo-treated dogs had already died.19

Fig. 8.