Fighting Alzheimer’s Disease with Galantamine

Memory is, therefore, neither Perception nor Conception,

but a state or affection of one of these, conditioned by lapse of time.

— Aristotle, On Memory and Reminiscence

Homer’s great epic of the ancient Mediterranean world, the Odyssey, was an oral history, argues mythologist Robert Graves.1 In his notable opinion, the ancient Greek myths are not merely esthetic and poetic creations, but records of events that took place and were forgotten by most — and would have been forgotten by all, had not Homer and others like him valued their preservation, telling and retelling the stories. In this way, the Odyssey is a tool for learning about mankind’s past triumphs and errors. It is also a tribute to the value and sanctity of memory.

The Birth of Consciousness

Odysseus, the King of Ithaca and the hero of these tales, is a hero of memory. The Greek word for mind or intellect or consciousness, nóos, is essential to his character, and its opposite, antinóos — defined as forgetfulness, stupidity, or arrogance — is the enemy of Odysseus. Forgetting, in the epic tales, is seen by Odysseus as an affront to memory and is punishable by severe reprisal, in which, as often as not, the perpetrator is killed. In his ten years of wandering throughout the known world, there are many adventures, but in the history of pharmacopoeia, one stands out: his encounter with the beautiful sorceress Circe on Aeaea, on her island home near Italy.

Memory Dilemma

When Odysseus and his crew arrive on Aeaea, they are tired of the hardships of travel and fearful for their safety. Deciding to reduce their risk, Odysseus remains with his ship while half of his crew ventures inland, where they meet Circe, who offers her “hospitality.” According to Homer, she serves up a banquet of food into which she mixes malignant drugs so that they might forget their fatherland and their desire to return to it. Then, with a wave of her hand, she turns them into swine.

Hearing of their plight, Odysseus sets out to free them. Along the way, in a forest glen, he is counseled by the god Hermes, in the form of a young man, who cautions him about dealing with Circe and gives him an antidote to protect him from the drugs that have taken down his crew. Hermes shows Odysseus the nature of the medicine, which has “a black root, but milk-like flower. The gods call it moly and it is difficult for men to dig up.”

Galantamine: The First Nootropic

According to a paper published in 1983, the drug given to the crew was likely to be an extract from the plant Datura stramonium (thorn apple, or jimsonweed). This makes sense, because not only were their memories taken from them, they were cast into a delusional-hallucinatory state during which they believed they had been turned into animals.2

Stramonium, among other drugs known to the ancient Greeks, is an anticholinergic that contains atropine and is known to produce such effects. Based on the description of the antidote moly, together with the immunity it gave Odysseus — thereby allowing him to rescue his crew from Circe and recover their memories — the researchers assert that moly is none other than the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor galanthamine (or galantamine, as it is now more commonly called), derived from the snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) and related species. Galantamine may be the first nootropic agent — a substance that enhances intelligent, purposive consciousness (nóos = consciousness, trope = a turning).

As further evidence, the researchers offer the site of the picking: a forest glen, where the snowdrop grows more readily because of the moist, sheltered ground.

The Snowdrop is small, inconspicuous, and difficult to find, flowering only briefly in the early spring. Its flower is milky-white, as indicated by the name Galanthus (gala = milk, anthus = flower), its root is dark, and its bulb, when peeled, is onion-like.

It can be found growing wild on the Balkan peninsula, including the Greek mainland and its islands, where it was thought to have originated. Also, the Greek physician and herbalist Dioscorides, who wrote the authoritative De Materia Medica, described the moly plant, (without ever acknowledging its epic use) in ways that substantiate its identity as Galanthus, from which galantamine is derived.

Galantamine’s Breakthrough: Alzheimer’s Disease Reversal?

The realization of Odysseus, Homer, and Dioscorides is ours too, when the value of two recent, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studies becomes apparent. Their welcome finding is that galantamine may be superior to any other cholinergic supplement. Galantamine may not only slow the decline into the black night of Alzheimer’s disease, but, for the first time, reverse it.

Snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis)

Keeping Memory Intact

While other evidence points to the antidotal use of other acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) — e.g., physostigmine (from Physostigma venonosum) for atropine toxicity — long before the underlying mechanisms were understood, the Homerian description reflects perhaps the earliest empirical knowledge of an AChEI in distant antiquity, about 3000 years ago.

As recent studies have shown, galantamine is one of the few long-lasting anticholinergic antidotes known, one that could easily have given Odysseus enough time to overpower Circe. In so doing, Odysseus liberates himself, his men, and their memories, giving them the courage and desire to go on. Thus, within this story and throughout the entire epic tale, the knowledge of the past is maintained and transmitted. Civilization is enriched by good history, artfully told, and we as its beneficiaries are less likely to repeat the errors of the past. So, it is when our memories remain intact.

The Dawn of Cholinergic Enhancement

Before the so-called consciousness revolution kicked into high gear in the 1960s, a little-known discovery occurred in the unlikely country of Bulgaria. In the 1950s, a Bulgarian pharmacologist noticed that local villagers made use of the wild-growing common snowdrop plant by rubbing it on their foreheads to ease nerve pain. Further investigation led to the isolation of an alkaloid extract of the snowdrop, galantamine, that helped inhibit acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme that breaks down acetylcholine (ACh).

An important nerve messenger, ACh is a biochemical that plays a role in muscle contraction and the maintenance of proper muscle tone; this was known throughout the world. Scientific literature indicates extensive use of snowdrop in Eastern Europe, such as Romania3 and the Ukraine,4 as well as the Balkan peninsula and other Mediterranean countries, where it was used topically and internally.5

At first, based on the surviving folkloric usage, galantamine was used in anesthesiology to increase muscle relaxation.6,7 Thereafter, it was rapidly introduced in other areas of medicine, such as neurology, ophthalmology, gastroenterology, intensive care and resuscitation, cardiology, and physiotherapy. For example, galantamine has been used successfully for the treatment of neuritis and neuralgia.8 Also intriguing is the ability of galantamine to increase color differentiation in monkeys,9 and it has been found to alleviate GI disturbances in rats.10

Cholinergic Plants for Healing

In nature, plants have evolved cholinergic compounds for self-defense, among other self-serving mechanisms. Humans in the ancient world soon learned to use these plants therapeutically for their maladies as well as for the age-related decline in acetylcholine activity.11 While few, if any, of these plants were adequately understood, dosing knowledge was usually refined by folk herbal doctors and wielders of magic, (often the same individuals).

Some plants were used, as Datura was used by Circe, for ritualistic, prophetic, or anesthetic purposes, or to investigate or perpetrate dementia and even madness. Among these other herbal cholinergics were Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade), Hyoscyamus niger (henbane), and Mandragora officinarum (mandrake). Long before the current biologically based hypothesis of cholinergic derangement in Alzheimer’s disease emerged, plants now known to contain cholinergic antagonists were recorded for their amnesia- and dementia-inducing properties.

Others have been used positively for healing, recuperation, and memory maintenance or memory recovery. These include Melissa officinalis (balm, containing choline)12 and Salvia officinalis (sage, containing choline)13 to enhance mental functions; Galanthus nivalis (snowdrop, containing galantamine) for muscle relaxation and memory restoration; and Panax ginseng (Chinese ginseng) and Panax quinquefolius (American ginseng) for age-related cognitive impairment.14 The active choline-like agents of the ginsengs have not yet been identified. Also, Ginkgo biloba contains active ingredients in the form of ginkgolides that have been found to possess antioxidant, neuroprotective, and cholinergic activities relevant to Alzheimer’s disease mechanisms.15

Alzheimer’s: Prevalent and Growing

According to the World Health Organization,16 around 35 million people in industrialized countries suffered from Alzheimer’s disease in 2010. As people live longer, the probability of contracting this disease increases with advancing “memory age.” It may thus be thought of as an age-related memory impairment (ARMI). Currently, the percentage of Alzheimer disease sufferers among those aged 65 to 69 is 1.4%, but between 85 and 89, the incidence reaches 21.6%. As we progress in our ability to stave off other so-called “diseases of aging,” which high levels of well-chosen dietary supplements can help to accomplish, there is still Alzheimer’s looming, not to mention other ARMIs, such as dementia.

Cholinergic Supplementation

As we have been aware for some time now, the use of cholinergic precursors such as choline and CDP-choline, cholinergic agonists such as DMAE, and cholinergic breakdown inhibitors such as GalantaMind™ may be able to put a brake on our decline into memory oblivion (see “Galantamine Reduces Alzheimer’s Genotoxicity and helps prevent brain cell death”), helping Alzheimer’s sufferers.

These common nutrients can help save us from mental perdition by helping to maintain proper cholinergic function. Not only are they derived from natural sources, they are virtually without side effects and with fewer problems than common food. As relatively new kids on the block, some acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) are synthetic drugs having no identical counterparts in the plant kingdom. Others are nutrients extracted from plants, and it is these that look more promising.

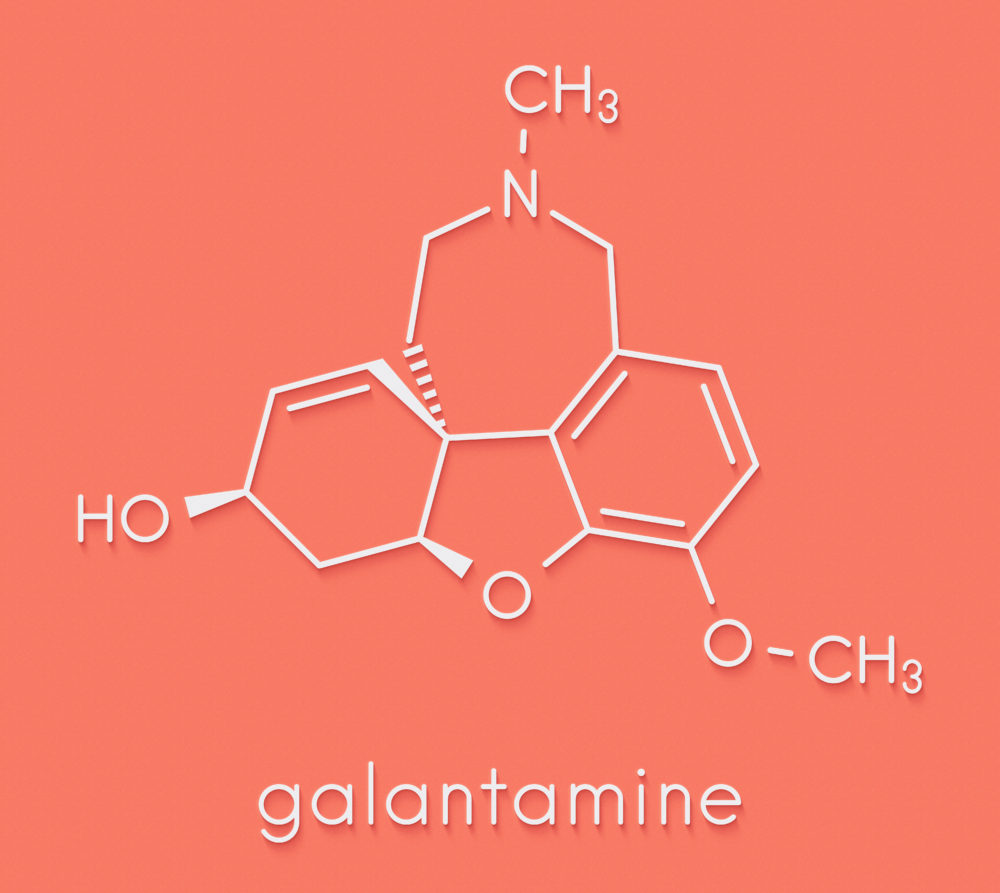

The structure of galantamine.

Alzheimer’s Cholinergic Disease

Although in use for several thousand years —with about 30 years of scientifically documented human studies —galantamine has only recently been looked at for its ability to alleviate one of the cholinergic problems common to us all as we age, and especially for those with Alzheimer’s. That problem is the progressive decline of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine in our brains and bodies caused by the enzyme acetylcholinesterase.

Galantamine helps preserve cholinergic function by effectively increasing the abundance of acetylcholine, which is required for proper memory function.

Unlike other AChEIs, however, galantamine can also have a positive influence on cholinergic function through improvement of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, the deterioration of which is largely unheralded as a mechanism of age-related memory decline.

Extensive Trials

Starting in 1985, galantamine underwent a series of clinical tests as a treatment for age-related impairment, dementia, and Alzheimer’s. But the quality of available Bulgarian snowdrops was dwindling, the extraction was time-consuming and expensive, and the yield was small. Also, wild snowdrop could not be patented. An Austrian group attempted to breed its own snowdrops, but the project was abandoned when a dramatic loss of the active substance was noted.

Because up to 10 grams per year of galantamine are needed per person, and the total annual crop of snowdrops was small, another source had to be found, and finally one was identified in the common daffodil (Narcissus pseudonarcissus L.). This source proved to be abundant and somewhat more economical.

Galantamine Triumphs

The two most dramatic clinical studies have just been published, and the results are better than expected. In the first study, 636 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease were given galantamine or placebo over a 6-month period.17 Of the study group, 62% were female, and the mean age was 75.

The trial was double-blinded and was conducted simultaneously at several different locations where the subjects were randomly assigned to galantamine or placebo. Doses were low at the start and were increased to either 24 or 32 mg/day. After the 6-month period, some patients were extended another 6 months, this time with open-label dosing at 24 mg/day.

At the end of the study, galantamine was found to have significantly improved cognitive function relative to placebo. Not only were baseline levels of cognition maintained, (about the same for both 24 and 32 mg/day) whereas the scores of those taking placebo declined at month 6, but the therapeutic response was not affected by those who have the genotype for Alzheimer’s.

After 12 months, the baseline for patients receiving galantamine at 24 mg/day on the open-label extension held: there was no further cognitive decline. In fact, patients taking galantamine improved significantly over their baseline scores. The cognitive performance of patients taking a placebo declined by about the same amount. This means that those taking galantamine not only held their ground, they improved.

Initial data suggest that the first signs of cognitive improvement are experienced in patients as soon as one week after reaching their target dose. Unlike synthetic AChEIs such as Tacrine® (THA), the side effects, primarily gastrointestinal, were minor and diminished over the months of the study. There was no evidence of any liver toxicity. Galantamine was found to improve cognition and global function significantly.

In the second study, galantamine was again tested using a slow dose escalation, this time over a period of 8 weeks, in 978 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease.18 Following a 4-week placebo run-in, the 8-week escalation proceeded in several locations, with random selection of those receiving galantamine or placebo in the double-blind trial. Those receiving galantamine were escalated to final maintenance doses of 8, 16, or 24 mg/day.

After 5 months, measurements were made with a variety of standardized assessment scales. At the end-point, those taking galantamine at 24 mg/day scored about 10% better than those at 16 mg/day. Compared to the placebo group, the differences were significantly better in the measure of cognition, daily activities, and behavioral symptoms. Adverse effects were of little significance in the galantamine groups. Because of its short half-life (calculated to be about 5 hours), galantamine was given twice per day, but three or four times per day might have been better.

|

Alzheimer’s Disease “Depending on where you set your sights, Alzheimer’s disease is a scientific puzzle, a medical whodunit, a psychological tragedy, a financial disaster, or an ethical, legal, and political dilemma. — Z. S. Khachaturian, Director of the Ronald and Nancy Reagan Research Institute of the Alzheimer’s Association. |

Alzheimer’s Improvement

A paper appeared in 1996 testing the hypothesis that the central feature of chronic fatigue syndrome is a cholinergic defect. The researchers chose galantamine to see if it could inhibit the irritability that this defect caused, believing that this played a large role in the pathogenesis of the illness.19 Of 39 subjects taking galantamine at 16 mg/day over an 8-week period, 43% reported a 50% improvement in their pain, sleep, and fatigue levels. A huge 70% reported 30% improvement, while the placebo group reported only 10% improvement. The improvements did not occur overnight, but gradually over 4 to 8 weeks.

Galantamine Reverses Alcohol-Free Learning Decline

At the Medical University in Sofia, Bulgaria, rats were fed a steady diet of alcohol for 16 weeks.20 After a 2-week pause, they were given galantamine, which was found to reverse the decrease in speed of learning and short-term memory induced by the alcohol. After 4 weeks of galantamine, there was significant improvement in the passive avoidance memory test and a maze test, as compared to the saline-injected alcoholic group. Galantamine improved the speed of learning, short-term memory, and spatial orientation in these alcohol-impaired rats.

Holy Moly: Bringing Up the Past

“Odysseus, the great teller of tales, launched out on his story,” begins the ninth book of the epic poem. In addition to having a great episodic memory, he is cast as a hero of memory, a great voyager, a hero of poetry, and a master of rhetoric. Memory is rhetoric (in the classical sense, the art of persuasion), entailing, per Aristotle, a thorough awareness of one’s audience. Thus, rhetoric involves the artistry of memory, and like poetry, is composed of one’s experiences, eidetic images, and the core abilities of the poet-remember-er. Thus, at the end of the journey, the heroic survival of Odysseus clearly demonstrates not only the importance of memory and of nóos (mind), but of poetry itself—and, by extension, of language and communication.

Moly (galantamine) is instrumental to the triumph of Odysseus, as it may be for you. And if memory is a tool for learning about our own past triumphs and errors, mastery of it is also a tribute to the value and sanctity of memory. And now you know where the expression “Holy Moly” comes from. Holy Moly is galantamine.

References

- Graves R. The Greek Myths. Penguin Books, Harmondworth, England, 1960.

- Plaitakis A, Duvoisin RC. Homer’s moly identified as Galanthus nivalis: physiologic antidote to stramonium poisoning. Clin Neuropharmacol 1983 Mar;6(1):1-5.

- Paskov DS. Nivalin: Pharmacology and Clinical Application. Medicina i Fizkultura, Sofia, 1959.

- Kalashnikov ID. Isolation of alkaloids from Galanthus nivalis Farm Zh 1970;25(3):40-4.

- Venturi VM, Piccinin GL, Taddei I. Pharmacognostic study of self-sown Galanthus nivalis (var. gracilis) in Italy. Boll Soc Ital Biol Sper 1965 Jun 15;41(11):593-7.

- Kirchev P, Stoyanov E. Studies in the activity of serum cholinesterase and histaminase in anaesthesia and surgical interventions. Nauchni Tr Vissh Med Inst Sofia 1966;45(4):27-34.

- Paskov DS, Stoyanov KA, Saev SK, Tenev AK, Mincheva.ML. Clinical experience with Nivalin as anticholinesterase drug in anaesthesiological practice. Proc First Eur Congr Anesthesiol, Vienna, Sept. 3-9, 1962.

- Strobbia R, Lalloni R, Dalzotto U The association of Nivaline with the vitamins of the B group (B1, B6, B12) and pyridoxal phosphate in the therapy of neuritis and neuralgia. Minerva Med 1968 Oct 27;59(86):4566-77.

- Dudkin KN, Kruchinin VK, Chueva IV, Noskov OF, Tonkopii VD. Th e effect of cholinergic substances on the mechanisms of visual recognition in monkeys. Zh Vyssh Nerv Deiat Im I P Pavlova 1990 Sep-Oct;40(5):968-73.

- Sirakov V, Kostadinova I, Velkova K, Kristev A. Roentgenographic study of ethosuximide-induced functional changes in rat gastrointestinal tract and their modulation by Nivalin in a chronic experiment. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 1998;40(4):71-7.

- Perry EK. Cholinergic phytochemicals: from magic to medicine. Aging Ment Health 1997;1(1):23-32.

- Wake G, Court J, Pickering A, Lewis R, Wilkins R, Perry E. CNS acetylcholine receptor activity in European medicinal plants traditionally used to improve failing memory. J Ethnopharmacol 2000 Feb;69(2):105-14.

- Perry EK, Pickering AT, Wang WW, Houghton PJ, Perry NS. Medicinal plants and Alzheimer’s disease: from ethnobotany to phytotherapy. J Pharm Pharmacol 1999 May;51(5):527-34.

- Lewis R, Wake G, Court G, Court JA, Pickering AT, Kim YC, Perry EK. Non-ginsenoside nicotinic activity in ginseng species. Phytother Res 1999 Feb;13(1):59-64.

- Perry EK, Pickering AT, Wang WW, Houghton P, Perry NS. Medicinal plants and Alzheimer’s disease: integrating ethnobotanical and contemporary scientific evidence. J Altern Complement Med 1998 Winter;4(4):419-28.

- http://www.who.int/

- Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Wessel T, Yuan W. Galantamine in AD: a 6-month randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a 6-month extension. The Galantamine USA-1 Study Group. Neurology 2000 Jun 27;54(12):2261-8.

- Tariot PN, Solomon PR, Morris JC, Kershaw P, Lilienfeld S, Ding C. A 5-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of galantamine in AD. The Galantamine USA-10 Study Group. Neurology 2000 Jun 27;54(12):2269-76.

- Snorrasson E, Geirsson A, Stefansson K. Trial of a selective acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, galanthamine hydrobromide, in the treatment of chronic fatigue syndrome. J Chron Fatigue Syndrome 1996;2(2/3):35-52.

- Iliev A, Traykov V, Prodanov D, Mantchev G, Yakimova K, Krushkov I, Boyadjieva N. Effect of the acetylcholinesterase inhibitor galantamine on learning and memory in prolonged alcohol intake rat model of acetylcholine deficit. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 1999 May;21(4):297-301.