Synergy – the story of GHRHs and GHRPS

Background – age-associated hGH insufficiency

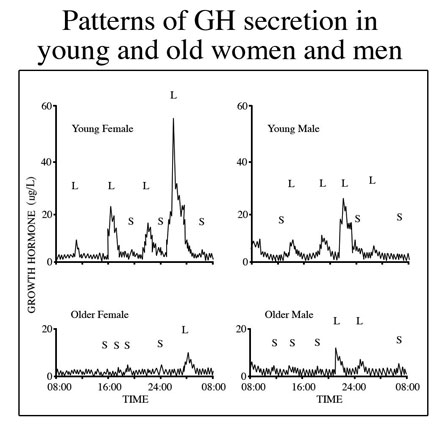

It is well known that serum titers of human growth hormone (hGH) decline during aging and that replacement of the hormone opposes many maladaptive changes in the body associated with senescence (Rudman et al., 1990). Thus, over the past two decades there has been extensive study of possible methods to overcome the hGH deficit so as to better prevent degenerative changes in the body that degrade form, function and quality of life. Originally, the most obvious and logical approach to therapy was administration of recombinant hGH. However, while effective in opposing undesirable changes in body composition and some other aspects of aging, hGH administration also brought with it certain undesirable side effects, abuse potential and regulatory liabilities (Walker, 2006). Regarding its use in age management, the major negative factor was that its administration as a bolus injection prevented simulation of the physiological pattern of secretion which is an important aspect of its functional profile in the body. Endogenous hGH is released in episodes that are essential for normal responses by its target tissues. These pulses attenuate with aging (Fig1).

Fig. 1: Growth hormone is released from the pituitary gland in “pulses” resulting from an interplay of stimulatory, (growth hormone releasing hormone) and inhibitory (somatostatin) signals from the brain. The pulses decline during aging, especially with loss of the nighttime surge of hormone release during slow wave sleep. The age-related decrease in mean serum hGH is primarily due to reduced pulse amplitude.

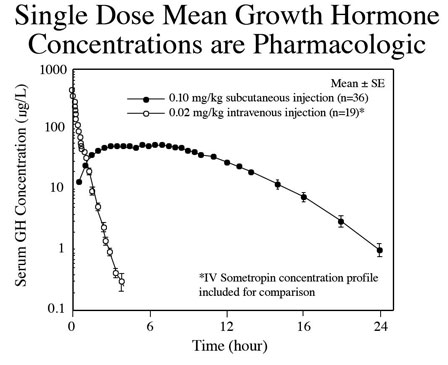

In contrast, exogenous hGH administration produces constant, non-physiological exposure that can result in tissue hyperstimulation, organ hypertrophy, hyperplasia and tachyphylaxis (Fig. 2).

Fig 2. Subcutaneous injection of recombinant hGH results in elevated levels of serum hormone that result in constant non-physiological stimulation of peripheral receptors. Intravenous administration has the same effect except that the hormone is cleared from the body more rapidly. Constant exposure to hGH resulting from pharmacological administration increases risk for side effects.

Paradoxically, exogenous hGH can also exacerbate aging in certain tissues such as the pituitary gland and brain because it presents strong negative feedback upon higher levels of the hGH neuroendocrine axis that “shut down” cellular functions causing disuse atrophy. Specifically this negative effect can be seen in those cells that secrete growth hormone releasing hormone (GHRH) from the hypothalamus, and those that produce endogenous hGH in the pituitary gland called somatotrophs.

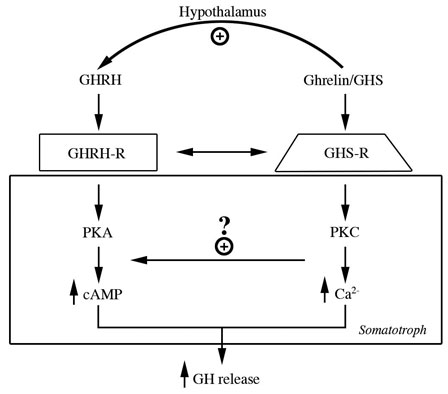

GHRH/Sermorelin

Because of negative issues associated with administering exogenous hGH as an antiaging, hormone replacement therapy, the use of secretagogues has become the currently favored approach. Simply put, secretagogues are substances that cause other substances to be secreted. This class of molecules is not limited to those capable of releasing hGH. In fact, secretagogues are commonly occurring, natural components of physiological systems. For example, gastrin is a major physiological regulator of gastric acid secretion and it also has an important trophic or growth-promoting influence on the gastric mucosa. In addition to gastrin, cholecystokinin binds the gastrin receptor which is a member of the G protein-coupled receptor family. Binding of gastrin stimulates an increase in intracellular Ca++, activation of protein kinase C (PKC), and production of inositol phosphate. The relevance of this information is that the relationship between two secretagogues as “fine tuners” of product secretion is a fairly common regulatory characteristic that is also seen in the hGH neuroendocrine axis. Furthermore, the G protein-coupled receptor that binds one category of hGH secretagogue called growth hormone releasing peptides (GHRP), also increases intracellular Ca++ and activates PKC with production of inositol phosphate.

Thus, we now focus upon hGH secretagogues as a more physiological approach to age-management medicine that provides for safe and effective restoration of growth hormone production and secretion during mid and later life. The evolutionary history of molecules currently available for hGH replacement therapy is quite interesting because the discovery of one was intentionally directed, while that of the other was totally serendipitous. The intentional search for the structure of the first secretagogue, GHRH, was led separately by Roger Guillemin and Andrew V. Schally who later shared the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for their work on neurohormones. They identified two forms of GHRH including GHRH-(1-44)-NH2 and GHRH-(1-40)-OH in human hypothalamic tissues (Ling et al, 1984). Subsequently, structure/activity relationships showed that the amino (NH2)-terminal, 29 residues of the GHRH molecules is involved in binding to its receptor and is responsible for biological activity. Further analysis demonstrated that cyclic adenosylmonophosphate (cAMP) is the intracellular second messenger affecting molecular events initiated by GHRH. Based upon this information, the synthetic analog, growth hormone releasing factor 1-29-NH2 (GRF1-29NH2) or sermorelin was developed for clinical application. In vitro studies demonstrated that GHRH and its analog sermorelin bind to the same saturable receptors on somatotrophs, initiate transcription of the hGH gene, and support hGH production and secretion by an intracellular mechanism involving cAMP. These findings indicated that GHRH and its analog sermorelin provide the primary stimulatory signal controlling hGH secretory dynamics in the pituitary gland.

GHRP/GHS

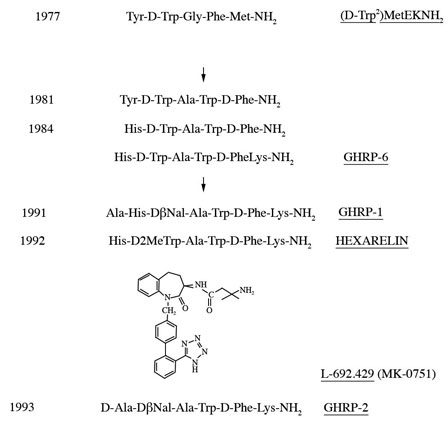

While Guillemin and Schally’s groups used comparable approaches to isolating and characterizing GHRH, Cyril Bowers who was an associate of Schally’s chose a novel method of discovery that was unrelated to extracting and fractionating tissues. Instead, Bowers chose to chemically modify the molecular structures of known neuroactive peptides assuming that some might be related to GHRH. Presumably, modest molecular changes in one or more of the known neuropeptides would help reveal the structure of GHRH. Accordingly, Bowers chose to modify the opioid pentapeptide, metenkephalin which resulted in synthesis of the first GHRP, Tyr-D-Trp-Gly-Phe-Met-NH2. However, its ability to release hGH from pituitary cells in vitro was very weak, causing many of Bowers colleagues to question whether the modest results were simply contamination artifacts. Nonetheless, he persisted in his research and synthesized a group of molecules with ever increasing hGH releasing potency that ultimately was found to represent a second, yet unknown hGH secretagogue totally different from GHRH. The evolution of these molecules is presented in Figure 3.

Fig 3. Evolution of molecules representing a second type of GH secretagoue (from Mueller et al. 1999)

Because of their chemical structures, the first of these molecules were called GH releasing peptides (GHRP’s). However, in the 1990’s investigators at Merck Pharmaceutical Co. synthesized non-peptidyl mimics, resulting in an alternative naming of the family of molecules as GH secretagogues (GHS’s). Results of early studies showed that the new molecules were neither GHRH, nor analogs of it because they bound different somatotroph receptors and employed a different intracellular second messenger (PKC not cAMP) (Fig 4).

Fig 4: Separate but interactive receptors for GHRH/sermorelin and GHRP/ghrelin exist on somatotrophs using complementary intracellular messengers to “fine tune” release of GH from the pituitary gland (Lengyel, 2006)

Based upon these differences and reminiscent of the relationship between morphine and endorphins, the search for an endogenous GHRP ligand was undertaken. Finally, in 1999, more than 20 years after GHRPs were synthesized; Masayasu Kojima and his group characterized a growth-hormone-releasing, acylated peptide from the stomach which he named ghrelin (Kojima et al., 1999). Although discovered in the stomach ghrelin was subsequently shown to be distributed throughout the body and to display various functions in addition to GH secretion (see van der Lely et al, 2004).

Data from early studies investigating the mechanism of action and relative potency of GHRPs on GH secretion did not represent their effects in the body as being significant. To the contrary the initial results of testing were equivocal. The reason for this mistake was that the initial studies were done in vitro, testing the effects of GHRPs alone on isolated pituitary cells. Not knowing at the time that there exists a synergistic relationship between GHRP and GHRH the early tests gave a significant underestimate of GHRP activity in vivo. In fact, the new molecules, especially GHRP-2 were actually capable of increasing serum hGH more than GHRH when tested in animals and especially in humans (Muller, 1999). The enhanced potency of GHRP in vivo suggested that it might be synergistic with GHRH and/or inhibitory upon somatostatin. Such effects would explain why GHRP-2 releases more hGH than that resulting from administration of GHRH alone. Evidence for this fact derived from animal studies in which endogenous GHRH was absent (Pandya et al. 1998, Popovic et al., 2003, Tannenbaum et al., 2003). One definitive demonstration of GHRH/GHRP synergy in vivo was provided using mice in which the GHRH gene was destroyed (Alba et al, 2005). These animals are called GHRH knockouts or GHRH-KO mice. Chronic administration of GHRP-2 to these KO mice, which was very potent in intact animals failed to stimulate somatotroph cell proliferation and GH secretion or to promote longitudinal growth in the knockouts. The data unequivocally demonstrated functional synergy between the two secretagouges in vivo. Since GHRP-2 failed to reverse the severe GHD caused by lack of GHRH in KO mice, it seemed that it must require at least some endogenous GHRH to be effective.

Having this information about GHRH/GHRP synergy from in vivo studies, we repeated the earlier in vitro studies, for the purpose of characterizing and differentiating the responses of primary cell cultures from rat pituitary glands to both GH secretagogues. Pituitary glands were collected from three month old Sprague Dawley rats, minced and enzymatically digested. The dispersed cells were plated, incubated for 24 hours after which time the primary cell cultures were washed with buffer and exposed to 10-10M sermorelin (GHRH), GHRP-6 or GHRH + GHRP-6 for hourly increments up to a maximum of 10 hours. GHRP-6 was readily available at the time and was used in lieu of GHRP-2 since their mechanisms are exactly the same. The GHRP’s differ only in potency. Controls were handled exactly the same as treated groups except that GH secretagogues were not added to the cell cultures. In these studies, intracellular and extracellular GH concentrations were estimated by Western blot analysis while GH messenger RNA (mRNA) was measured by Northern blot analysis.

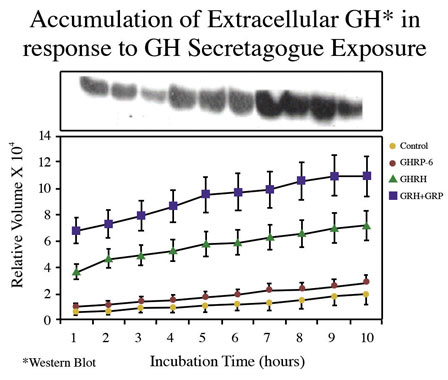

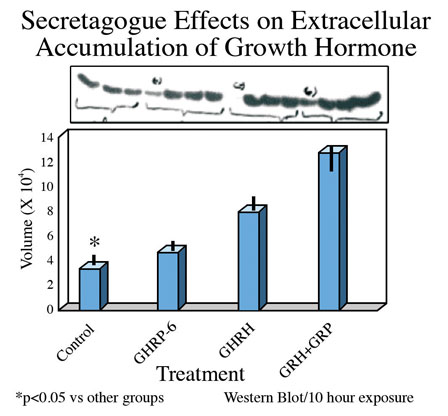

Consistent with earlier reports, GHRP-6 alone was a weak releaser of GH from pituitary cells compared to GHRH alone or GHRH + GHRP-6. Only a slight, statistically insignificant increase in extracellular accumulation of GH occurred in media containing cells exposed to GHRP-6 compared to unstimulated control cells (Fig 5).

Fig 5A. Comparison of hourly increases in GH concentrations in media containing pituitary cells and GH secretagogues

Fig 5 B: Mean concentrations of GH in media containing pituitary cells after 10 hours exposure to GH secretagogues.

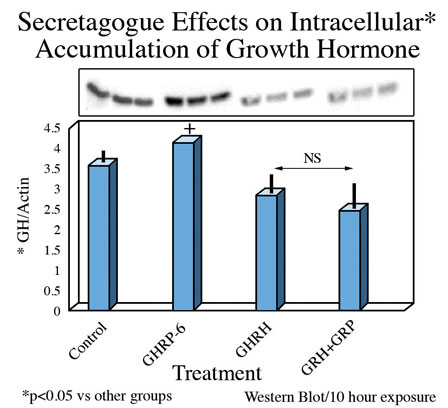

On the other hand, intracellular concentrations of GH were greatest in rat pituicytes that were exposed to GHRP-6 alone, compared to their controls or to those exposed to sermorelin or GHRH + GHRP-6 (Fig 6).

Fig. 6: Intracellular concentrations of GH in cells exposed for 10 hours to GH secretagogues alone or in combination.

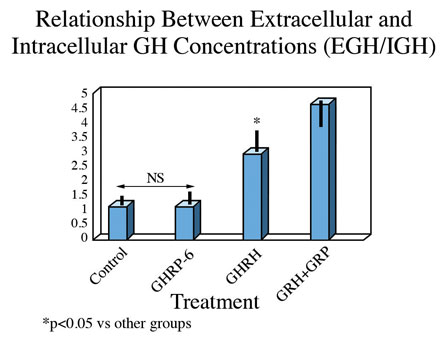

These observations suggest that either translation of the GH gene is occurring more in unstimulated and GHRP-6 exposed cells than in those exposed to GHRH or GHRH + GHRP, or that the latter two groups are secreting more GH than the former two. This possibility was confirmed upon subsequent analysis. In fact, the ratio of extracellular to intracellular GH was the same for control and GHRP-6 exposed cells, whereas it was significantly greater in those exposed to GHRH or GHRH + GHRP-6 (Fig. 7). This observation means that there occurred an increased release of GH from cells exposed to GHRH and GHRH + GHRP-6 compared with GHRP-6 alone.

Fig 7. Ratio of extracellular to intracellular GH in pituitary cells exposed to GH secretagogues for 10 consecutive hours. Data show that the amount of GH leaving somatotrophs exposed to media or media containing GHRP alone is relatively small, whereas it is significantly greater in cells exposed to GHRH and especially in those exposed to combinations of GHRH and GHRP

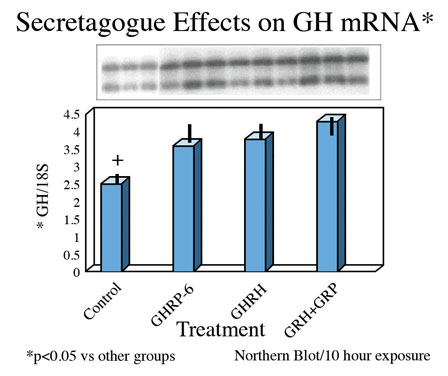

Finally, exposure of rat pituicytes to GHRP-6 was associated with increased accumulation of GH mRNA approximately equal to that associated with exposure to GHRH. Mean concentrations of GH mRNA in cells exposed to GHRH + GHRP were greater than for either peptide alone (Fig 8)

Fig.8: Effects of GHRH and GHRP alone or in combination on transcription of GH gene in pituitary cell cultures. Both secretagogues stimulate accumulation of messenger RNA compared to control conditions. Combination of both secretagoges increased mRNA production more than either secretagogue alone.

The results of these studies indicate that GHRP stimulates transcription and/or translation of GH mRNA thereby increasing the gene product and GH intracellular stores. However, GHRP alone does not stimulate GH release. Instead, when GHRP is tested in vitro, GH leaves the cell passively due to increasing intracellular GH concentrations that eventually exceed the threshold for spontaneous release. This conclusion is supported by the fact that the ratio of extracellular to intracellular GH is the same in control and GHRP-6 exposed cells. Thus, unlike GHRH, which actively promotes GH release, GHRPs have minimal effect on GH secretion, but significantly affect its production. In this sense, GHRP-6 is not a secretagogue, per se. This fact explains why the GHRPs appear inactive when tested alone in vitro or in animals lacking endogenous GHRH. However, GHRP enhances the secretagogue effect of GHRH/sermorelin by increasing intracellular stores of GH which provides a larger pool for active release by sermorelin. Perhaps GHRPs also directly enhances the GHRH secretory function, but that possibility has not yet been tested. In any event, these studies in conjunction with in vivo studies demonstrate that for GHRPs to be clinically effective, the sermorelin/GHRH receptor must be active. Conversely, sermorelin/GHRH action on somatotroph cells is not influenced by blockage of the GHRP receptor demonstrating the primary and secondary/modulatory roles of GHRH and GHRP’s, respectively (Kamegai et al., 2004). This information is particularly relevant to clinical applications for GHRP-2 in aging because GHRH titers decline but do not disappear completely as we grow old. Thus, GHRP-2 can be used by itself in age-associated hGH insufficiency to restore effectiveness of the remaining endogenous GHRH and thereby to promote recrudescence of the hGH neuroendocrine axis and oppose maladaptive effects of senescence. However once levels of endogenous GHRH become critically low, then an appropriate clinical approach to restoring GH neuroendocrine activity would be to provide combinations of sermorelin and GHRP-2 as seen in (Figure 9).

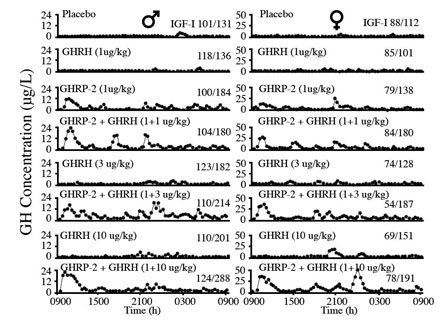

Fig 9: Effects of 24 hour infusion of GH Secretagogues on GH secretory patterns and IGF-1 levels in elderly men and women. GHRP-2 has a greater effect than GHRH on increasing the amplitude of GH pulses. Attenuation of these pulses is a significant detrimental change associated with aging. (Bowers, et al, 2004)

In addition to its synergistic effect with GHRH, GHRP-2 simulates the normal, physiological secretory profiles of hGH which is markedly pulsatile in all species that have been studied (see Muller et al., 1999). The pulsatile pattern of secretion which is essential for hGH efficacy becomes blunted with age and it eventually ceases. This effect is more due to the dynamics of endogenous GHRH secretion than to its absence from the body. Relevant to the previously mentioned synergistic effect of GHRP-2 and endogenous GHRH is the fact that GHRP-2 amplifies the naturally occurring pulsatile GH secretion that becomes diminished as the relative concentrations of GHRH decline with age (Figure 8). In the short term, i.e., over a period of 24 hours, Bowers et al (2004) showed that the combination of GHRH and GHRP gives best return to pulsatility, but over the longer term as pituitary recrudescence occurs then the need to administer exogenous GHRH along with GHRP-2 may become less significant. This is true except in cases of severe GHRH deficiency. Then oral GHRP-2 can be supplemented with sermorelin sublingual for chronic therapy.

GHRP-2 Safety

Published reports of the beneficial effects of potent ghrelin analogs such as GHRP-2 on the body support it being an integral part of age-management medicine. Clearly because of its ability to enhance production and secretion of endogenous hGH, GHRP-2 can provide long-term therapy for opposing degenerative changes in the body such as muscle loss as well as for a number of other dysfunctional changes. This potential relates to the ability of GHRP to stimulate of appetite and growth (Mericq, V.N., et al. 1998; Laferrere, B. et al., 2004), control gastric motility and secretion, module pancreatic and immune functions, glucose metabolism, cardiovascular performance, sleep and behavior (see Van Der Lely, A.J. et al. 2004). To be an effective agent for opposing the unending progression of senescence, GHRP-2 should be used as a daily, on-going component of therapy. However, this recommendation for chronic administration of the peptide raises the question of compliance and especially of safety.

Heretofore, secretagogues have been commonly administered by subcutaneous injection which is not conducive to elective, prophylactic therapy lasting for years. However, this mode of administration is not required for efficacy. Instead the idea that parenteral administration is necessary derives from tradition and the idea that peptides cannot be orally ingested because they are subject to inactivation by endopeptidases. However, understanding that the peptide structures of GHRPs contain D-amino acid isomers which are not substrates for these enzymes, we showed that the secretagogues are orally bioavailable and can be included with other supplements as a part of daily anti-aging therapy (Walker, 1990). This fact provides support for formulation of patient compliant, oral supplements containing GHRP-2 that provide long-term anti-aging therapy. Should combination secretagogue therapy be necessary, a bioavailable, sublingual formulation of sermorelin has also been formulated.

But what of safety, does the toxicity profile of GHRP-2 favor its long-term use? Extensive review of the endocrine and toxicology literature failed to identify any reports of general or reproductive toxicity nor of carcinogenicity for GHRP-2 in animals or humans. The peptide has been used clinically for three decades for its physical and functional benefits including but not limited to improved body composition, sleep, immune function, cardioprotection, etc. (Van der Lely et al, 2004) without any evidence of adverse events. For the most part, lack of toxicity has been reported in peer-reviewed studies performed for therapeutic purposes (Bowers et al. 2004; Pihoker et al., 1998; Van den Berghe et al., 1997) even when administered at relatively high daily doses for as long a year. However, to ensure the safety of GHRP-2, the literature search was expanded to examine side effects for ghrelin which should also represent toxicity of its GHRP analogs. Thus, in addition to effects following stimulation of the pituitary, GHRP-2 pathophysiological effects might occur in ghrelin target sites including the stomach, GI tract, pancreas, heart and brain. However, none were found suggesting that the molecules are relatively free from side effects. Published support for this view derives from a study showing that pre-pubertal children weighing on average 45 kg, received 900 µg/kg GHRP-2 orally, twice daily without experiencing any adverse effects (Mericq et al., 2003). Finally, to determine if GHRP-2 might be reasonably designated as generally regarded as safe (GRAS) for human consumption, we performed a series of general toxicity and genotoxicity studies on the peptide (Walker and Saini, 2014). The results of those were negative in every case and consistent with the absence of reports of adverse events for GHRP-2 in the literature. Using standard screening assays for genotoxicity including AMES, micronucleus, and chromosomal aberration studies, no evidence of mutagenicity could be demonstrated. In addition, acute or chronic in vivo toxicity did not occur in experimental animals at even the extremely high doses of 2000 mg/kg (GHS-5/unclassified category) or 50 mg/kg (NOAEL), respectively. When converting Animal Dose in mg/kg to Human Equivalent Dose (HED), regulatory guidelines recommend that when HED is based upon rat NOAELS, either divide the animal dose by 6.2 or multiply it by 0.16 (US FDA, 2005). Based upon this recommendation, a NOAEL for human clinical application of GHRP-2 would be approximately 8 mg/kg. Heretofore, the highest therapeutic dose administered orally to human beings for as long as one year was 0.9 mg/kg twice daily (or 1.8 mg/kg/day). It has been administered intranasally for twice as long without any evidence of side effects (Pihoker et al., 1997). While effective in stimulating growth hormone for realization of its intended clinical benefits, the risk of dose-related adverse events occurring at the therapeutic doses was non-existent. Furthermore, doses as low as 4 mg orally or 1 mg subcutaneously per day which are currently being used to sustain lean body mass during aging are equivalent (based upon a 60 kg human being) to only 0.07 or 0.02 mg/kg/day, respectively. Thus, the absence of publications reporting side effects in human subjects receiving GHRP-2 is not surprising. In conclusion, the findings of studies reported herein, taken in conjunction with a history of three decades use in human subjects without a single report of toxicity in the peer-reviewed literature, support the view that the peptide is safe and effective for age management as a component of medical foods or nutritional supplements.

GHRP-2 Efficacy

While GHRP-2 mimics many of the physiological effects of ghrelin, it has received greatest attention clinically for its potent hGH releasing activity. One possible application for that effect is treatment of sarcopenia that occurs in everyone as they grow old. Sarcopenia is a serious and global threat to health and quality of life in aging populations. Characteristic of sarcopenia is spontaneous and progressive muscle weakness with actual loss of lean body mass that contributes significantly to frailty, loss of functional mobility and independence as well as increased risk for development of intrinsic disease (Doherty T., 2003; Roubenoff R., 2001; Roubenoff R and Hughes V.A., 2000). In fact, erosion of skeletal muscle mass occurs in as much as 30% of the population beyond the age of 60 years. While sarcopenia is known to result from multiple factors, including age-related GH insufficiency, there are currently no commercially available products that provide a means to replace anabolic hormones as a means of therapy. However, the link between sarcopenia, disability and pathology among elderly men and women highlights the importance of developing all effective and safe means including endocrine therapies that are possible to oppose its progression during aging.

The possible benefits of GHRP-2 were tested in a double blinded, placebo controlled clinical trial involving 75 healthy subjects ranging in age from 40 to 68 years. The following data resulted from that 90 day study (Walker and Saini, 2014).

Mean concentrations of serum insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) significantly increased from 103.54 ± 1.94 ng/mL at baseline to 111.40 ± 2.01 ng/mL at day 45. Levels further increased to 120.47 ± 2.10 ng/mL after 90 days of treatment. In contrast, there were no significant changes in IGF-1 levels in subjects receiving placebo.

Body Mass Index (BMI) and total body water did not change significantly in either treatment or placebo groups during the course of study.

Total body fat was significantly decreased in the treatment group from 34.46 ± 1.23 % at baseline to 32.54 ± 1.04 % on day 45 and to 31.31 ± 1.11 % at the end of treatment. The decrease in body fat after 45 days of treatment was 5.57% and after 90 days it decreased 9.14%. Visceral fat decreased in the treatment group from 11.84 ± 0.66 % at baseline to 10.62 ± 0.66 % on day 45 and to 10.15 ± 0.67 % after 90 days of GHRP-2 administration. Visceral fat was reduced by 10.3% and 14.27% after 45 and 90 days of treatment, respectively. There were no changes in total or visceral body fat within the placebo group.

Muscle mass was significantly increased from 41.88 ± 1.28 Kg at baseline to 44.13 ± 1.24 Kg at the end of the 90 day treatment period. Lean body mass increased by 5.37% after 90 days treatment with GHRP-2 in comparison to placebo which was not associated with change in muscle mass.

Forced vital capacity (FVC) significantly increased by 16.61% after 90 days of treatment. FVC was significantly increased from 71.84 ± 3.18 % at baseline to 73.60 ± 3.52 % on day 45 and to 83.77 ± 3.70 % on day 90. There were no changes in FVC in the placebo group throughout the course of study.

Favorable changes were measured in the treatment group for bone mass and grip strength but these did not reach the level of statistical significance. No changes in bone mineralization or cardiovascular compliance were noted in either group. It is possible that longer treatment periods are required to gain positive effects for these clinical parameters.

Changes in Quality of Life(QoL) were measured using standardized questionnaires that were completed by all subjects at baseline and on days 45 and 90 of study. There was a significant improvement in QoL for both treated and control groups but the effect occurred in 96% of those receiving treatment as compared with only 60% of those receiving placebo. Of those showing improvement, most remarked about having increased energy, improved work ability/capacity, increased confidence, improved physical fitness, increased resistance towards illness, increased sleep duration and overall feelings of happiness. A few of subjects reported having reduced back pain and ankle pain while others remarked about improvement in skin texture and radiance.

Changes in pancreatic function as evaluated using the Intravenous Glucose Tolerance Test (IGTT) suggested that insulin sensitivity was increased in the treatment group. This conclusion based upon the fact that mean glucose levels were in the normal range at base line before glucose administration, but spiked significantly by one minute afterward. Thereafter, blood glucose returned to normal levels within two hours. A similar profile occurred after 30 days on study both in treated and placebo subjects. However, insulin levels were 24.62 % and 32.94 % lower at 1 hour and 2 hours, respectively, after glucose administration in the treatment group as compared to 3.4 % and 7.25 % lower in the placebo group. Despite the lower insulin levels in the treated individuals, their blood glucose levels were comparable to those in the placebo group suggesting the treatment increased insulin sensitivity.

Conclusions

Because of their effects on body composition, GH secretion, appetite and energy metabolism the GH secretagogues such as GHRP-2 and sermorelin are appropriate for various applications in age management including for use in nutriceuticals or “medical food” formulations to treat sarcopenia, a major threat to health and vitality in the elderly (Doherty, T.J., 2003). Because of its link with disability, the need to develop effective pharmacological and nutritional interventions that along with resistance exercise may prevent or partially reverse sarcopenia, is evident. Since GH secretagogues are known to stimulate production of GH by the pituitary and also to restore natural, physiological, episodic release of the hormone, they have the potential to complement resistance exercise as well as amino acid and protein supplements as another beneficial factor for opposing many age-associated dysfunctions. Accordingly, they can be included in future formulations of food supplements that currently use molecules such as the anti-catabolic metabolite of leucine, calcium ß-hydroxy-ß-methylbutyrate (CaHMB) and other such substances. The only currently available oral supplement containing a GH secretagogue is GHRP2-Pro™, which holds great promise for treating sarcopenia and many of the other maladaptive consequences of aging.

References

1. Alba M, Fintini D, Bowers CY, Parlow AF, Salvatori R. Effects of long-term treatment with hormone-releasing peptide-2 in the GHRH knockout mouse. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2005, 289:E762-E767. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00203.2005

2. Bowers CY, Granda R, Mohan S, Kuipers J, Baylink D, Veldhuis J. Sustained elevation of pulsatile growth hormone secretion and IGF-1 concentratinos during subcutaneous administration of GHRP-2 in older men and women. J Clin Endo Metab 2004, 89:2290-2300.

3. Doherty, T.J., 2003. Invited Review: Aging and Sarcopenia. J. Appl. Physiol. 95, 1717–1727; doi:10.11